System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

Ever experienced a sudden crash, a blackout, or a complete digital meltdown? That’s system failure in action—unpredictable, disruptive, and often costly. In our hyper-connected world, understanding its roots and remedies isn’t just smart—it’s essential.

What Is System Failure?

A system failure occurs when a system—be it mechanical, digital, organizational, or biological—ceases to perform its intended function. This breakdown can be temporary or permanent, localized or widespread. From a crashing laptop to a nationwide power outage, system failure manifests in countless ways, often with cascading consequences.

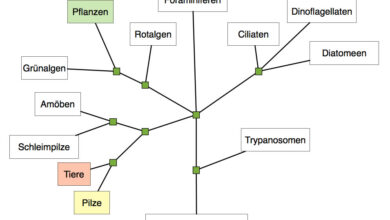

Defining System and Functionality

A ‘system’ refers to any interconnected set of components working together toward a common goal. This could be a computer network, a transportation grid, or even the human body. When one or more components fail to operate correctly, the entire system may falter. The failure isn’t always about hardware—it can stem from software bugs, human error, or design flaws.

- Systems are built on interdependence: one weak link can compromise the whole.

- Functionality depends on both design integrity and operational consistency.

- Failures can be latent (hidden) or acute (immediate).

Types of System Failure

System failure isn’t a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. It can be categorized based on cause, scope, and impact. Common types include:

- Hardware failure: Physical components like servers, circuits, or engines break down.

- Software failure: Bugs, crashes, or incompatibilities disrupt operations.

- Network failure: Connectivity loss in communication systems.

- Human-induced failure: Mistakes in operation, configuration, or maintenance.

- Environmental failure: Natural disasters or extreme conditions triggering collapse.

“Failures are finger posts on the road to achievement.” – C.S. Lewis

Common Causes of System Failure

Understanding the root causes of system failure is the first step toward prevention. While each incident is unique, certain patterns emerge across industries and technologies.

Design Flaws and Poor Architecture

Many system failures originate at the drawing board. Inadequate planning, lack of redundancy, or flawed logic in system architecture can create vulnerabilities that only surface under stress. For example, the NASA Mars Climate Orbiter failed in 1999 due to a unit mismatch—engineers used imperial units while the software expected metric.

- Single points of failure (SPOF) increase risk.

- Lack of scalability leads to overload under peak demand.

- Poor error handling allows small issues to escalate.

Software Bugs and Glitches

Even the most rigorously tested software can harbor hidden bugs. A single line of faulty code can trigger a system failure with global implications. The 2012 Knight Capital Group incident, caused by outdated deployment scripts, led to a $440 million loss in 45 minutes due to uncontrolled trading algorithms.

- Memory leaks, race conditions, and infinite loops are common culprits.

- Third-party dependencies can introduce unseen vulnerabilities.

- Insufficient testing in real-world scenarios increases risk.

System Failure in Technology and IT Infrastructure

In the digital age, IT systems are the backbone of nearly every organization. When they fail, the consequences can be catastrophic—data loss, financial damage, reputational harm, and legal liability.

Server and Data Center Failures

Data centers house the servers that power websites, cloud services, and enterprise applications. A failure here can bring entire businesses to a halt. In 2021, a major AWS outage disrupted services like Slack, Airbnb, and Netflix due to a networking issue in the US-EAST-1 region.

- Power supply failures are a leading cause of downtime.

- Cooling system malfunctions can lead to hardware overheating.

- Network misconfigurations can isolate critical systems.

Cybersecurity Breaches as System Failure

Cyberattacks don’t just steal data—they can cause full system failure. Ransomware, DDoS attacks, and zero-day exploits can cripple networks, encrypt critical files, or redirect traffic maliciously. The 2017 NotPetya attack, initially targeting Ukraine, caused over $10 billion in global damages by paralyzing logistics, healthcare, and finance systems.

- Phishing and social engineering bypass technical defenses.

- Unpatched software creates exploitable entry points.

- Lateral movement within networks amplifies damage.

“It’s not a matter of if, but when a cyberattack will happen.” – Kevin Mandia, FireEye CEO

System Failure in Critical Infrastructure

When essential services like power, water, or transportation fail, the impact extends far beyond inconvenience. Lives can be at risk, economies disrupted, and public trust eroded.

Power Grid Failures

Electricity is the lifeblood of modern society. A failure in the power grid can trigger a domino effect—hospitals lose backup power, traffic lights go dark, and communication networks fail. The 2003 Northeast Blackout affected 55 million people across the U.S. and Canada, caused by a software bug and inadequate monitoring.

- Overloaded transmission lines can trigger cascading failures.

- Aging infrastructure increases vulnerability.

- Lack of real-time monitoring delays response.

Transportation System Collapse

From air traffic control systems to railway signaling, transportation relies heavily on integrated technology. In 2015, a software glitch in the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) system caused a nationwide ground stop, stranding thousands of passengers.

- Synchronization errors can lead to collisions or delays.

- Legacy systems are harder to maintain and upgrade.

- Interoperability between agencies is often lacking.

Organizational and Human Factors in System Failure

Even the most advanced technology can’t compensate for poor management, communication breakdowns, or human error. People are both the designers and operators of systems, making them central to both success and failure.

Human Error and Procedural Lapses

Mistakes happen—but in high-stakes environments, they can be catastrophic. The Chernobyl disaster in 1986 was partly due to operators disabling safety systems during a test. Similarly, in 2018, a British Airways IT failure grounded 75,000 passengers due to an engineer accidentally disconnecting a power supply.

- Lack of training increases the risk of misoperation.

- Overconfidence in automation reduces vigilance.

- Poor documentation leads to incorrect procedures.

Organizational Culture and Complacency

A culture that discourages reporting errors or resists change can foster systemic weaknesses. The 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger explosion was not just an engineering failure—it was a failure of organizational culture. Engineers had warned about O-ring risks in cold weather, but their concerns were ignored.

- Pressure to meet deadlines can override safety protocols.

- Groupthink prevents critical evaluation of risks.

- Leadership must foster transparency and accountability.

“The root cause of every major accident is management failure.” – Dr. Sidney Dekker

Preventing System Failure: Best Practices

While no system can be 100% failure-proof, robust strategies can significantly reduce risk and improve resilience.

Redundancy and Failover Mechanisms

Redundancy means having backup components that take over when the primary system fails. This is standard in aviation, data centers, and medical devices. For example, airplanes have multiple hydraulic systems; if one fails, others can maintain control.

- Geographic redundancy protects against regional disasters.

- Load balancing distributes traffic to prevent overload.

- Automated failover ensures minimal downtime.

Regular Maintenance and Monitoring

Proactive maintenance identifies issues before they escalate. Predictive analytics, sensor networks, and routine audits help detect anomalies early. The aviation industry uses continuous monitoring to assess engine health and schedule repairs.

- Scheduled updates prevent software decay.

- Real-time dashboards provide instant visibility.

- Log analysis helps trace the root cause of issues.

Case Studies of Major System Failures

History offers powerful lessons through real-world examples of system failure. Analyzing these incidents reveals patterns, vulnerabilities, and opportunities for improvement.

The 2003 Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster

During launch, a piece of foam insulation broke off and damaged the shuttle’s wing. Upon re-entry, superheated air penetrated the structure, causing the shuttle to disintegrate. The failure wasn’t just technical—it was cultural. NASA had normalized foam shedding, ignoring repeated warnings.

- Normalization of deviance: accepting small risks as routine.

- Lack of in-flight inspection capability.

- Communication gaps between engineering and management.

Toyota’s Unintended Acceleration Crisis

Between 2000 and 2010, Toyota faced lawsuits over vehicles accelerating uncontrollably. Investigations revealed a mix of mechanical issues (sticky pedals) and software flaws in electronic throttle controls. The crisis cost over $5 billion and damaged brand trust.

- Complex systems made root cause analysis difficult.

- Delayed response worsened public perception.

- Software transparency became a critical demand.

Recovery and Resilience After System Failure

When failure occurs, how an organization responds determines the long-term impact. Recovery isn’t just about fixing the system—it’s about restoring trust, learning from mistakes, and building resilience.

Incident Response and Crisis Management

A structured incident response plan is crucial. It should include clear roles, communication protocols, and recovery steps. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework provides guidelines for identifying, protecting, detecting, responding, and recovering from incidents.

- Designate a crisis response team with defined responsibilities.

- Communicate transparently with stakeholders.

- Conduct post-mortems to prevent recurrence.

Building a Resilient System Culture

Resilience goes beyond technology—it’s about mindset. Organizations must foster a culture where failure is seen as a learning opportunity, not a blame game. Google’s Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) model embraces this by encouraging blameless post-mortems.

- Encourage open reporting of near-misses.

- Invest in continuous training and simulation.

- Promote cross-functional collaboration.

“Resilience is not about bouncing back, but about learning forward.” – Karl Weick

What is the most common cause of system failure?

The most common cause of system failure is human error, often compounded by poor design, lack of training, or inadequate procedures. However, in digital systems, software bugs and cybersecurity vulnerabilities are increasingly prevalent.

Can system failure be completely prevented?

While it’s impossible to eliminate all risks, system failure can be significantly mitigated through redundancy, rigorous testing, proactive maintenance, and a strong safety culture. The goal is resilience, not perfection.

How do organizations recover from a major system failure?

Recovery involves immediate incident response, root cause analysis, system restoration, and communication with stakeholders. Long-term recovery includes process improvements, staff training, and rebuilding public trust.

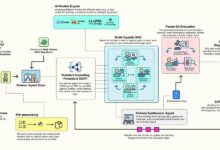

What role does AI play in preventing system failure?

AI enhances predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and automated response. Machine learning models can analyze vast datasets to identify patterns that precede failure, enabling proactive intervention before breakdowns occur.

Why is system failure in critical infrastructure so dangerous?

Because critical infrastructure supports essential services like healthcare, transportation, and communication, its failure can endanger lives, disrupt economies, and create widespread chaos. The interconnected nature of modern systems means one failure can cascade across sectors.

System failure is an inevitable reality in complex systems, but it doesn’t have to be catastrophic. By understanding its causes—from design flaws to human error—and implementing robust prevention and recovery strategies, organizations can build more resilient, reliable systems. The key lies in vigilance, preparation, and a culture that values learning over blame. As technology grows more intricate, so must our approach to safeguarding the systems we depend on.

Further Reading: